Admittedly, the recent riots in Athens made us all reflect on the uses of our monumentalized past (and its tangible symbols), since they involved some ot the city's most splendid listed buildings. The Academy, the University Central, the National Library, the School of Fine Arts, the National Museum, all faced clear and present danger by angry youths who chose to express their disaffiliation from Greek society through fire. Although the rioters expressed their anger mostly against banks and department stores, at least one library was torched (that of the Law School, by accident it would seem, owing to its being situated above a fancy shop specializing in top-dollar menswear). Still, many Athenians and frustrated visitors despaired in the sight of a National Library or Museum under attack (these attacks never materialized, though it seems that some of the rioters did try to attack such august targets). Many feared that the Nation's treasured monuments, the pinacles of Athenian neoclassicism and the precious few remains of the glory that was Greece were under attack by the youth of Greece itself, turning their back to the past (or is it the future?).

Admittedly, the recent riots in Athens made us all reflect on the uses of our monumentalized past (and its tangible symbols), since they involved some ot the city's most splendid listed buildings. The Academy, the University Central, the National Library, the School of Fine Arts, the National Museum, all faced clear and present danger by angry youths who chose to express their disaffiliation from Greek society through fire. Although the rioters expressed their anger mostly against banks and department stores, at least one library was torched (that of the Law School, by accident it would seem, owing to its being situated above a fancy shop specializing in top-dollar menswear). Still, many Athenians and frustrated visitors despaired in the sight of a National Library or Museum under attack (these attacks never materialized, though it seems that some of the rioters did try to attack such august targets). Many feared that the Nation's treasured monuments, the pinacles of Athenian neoclassicism and the precious few remains of the glory that was Greece were under attack by the youth of Greece itself, turning their back to the past (or is it the future?).

The exhilarating torching of the city's Christmas tree - a monument to our collective determination to celebrate Christmas and "have a good time" no matter what - was a poignant blow to the state's obession with monumentalizing itself: many enjoyed the symbolism of the event, many were shocked by what they saw as unecessary cruelty.

The displaying of a banner calling for "resistance" up on the Acropolis, an act of protest with a recent more famous precedent, was castigated as "blasphemous" by the usual champions of public order and good taste overall, and the vandalism of public buildings and statues was mourned by most of us - if only when one considers the hefty restoration costs.

What I found most interesting, however, was that at the time when angry protesters destroyed public monuments - erected in honour of events and institutions that they felt had nothing to do with them - or appropriated others (the Acropolis) in the hope that their voice might be heard, NEW monuments were in the process of being erected in Athens; and no, I don't mean the new Christmas tree hastily erected by our defiant mayor...

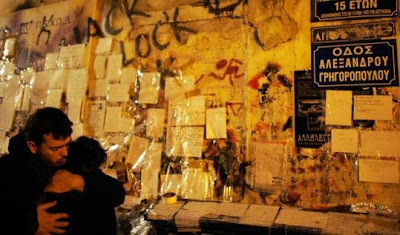

While municipal services were busy elsewhere, and riot police was entrusted with the protection of the city's site of festivities, some other Athenians re-named, albeit unoficially, the street where the boy was killed. Although it started as a pre-modern declaration of veneration, the monument produced is thoroughly modern. Little by little, the site became a "site", with a clear outline, visitors, snap-shot takers (incuding myself, of course) while unseen curators covered the exhibited notes in plastic to preserve them for posterity.

So, brothers, do not despair. The Museum, one of modernity's central pillars, is alive and well. Yes, some museums might perish here and there; yes, some sites might get to know the "wrong kind" of appropriation; and, true, most of the rioters and sympathizers wouldn't be seen dead in a museum or a national heritage site (unless they carried a banner of protest). So what? As long as NEW monuments are created the good old way, not everything has been lost. Curators will always be needed and conservators will get new assignments.